Lent 2012

Pope Benedict XVI's Message

(cf Heb 10, 24) - in Arabic, English, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese & Spanish

“Let us be concerned for each other, to stir a response in love and good works”

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

The Lenten season offers us once again an opportunity to reflect upon the very heart of Christian life: charity. This is a favourable time to renew our journey of faith, both as individuals and as a community, with the help of the Word of God and the Sacraments. This journey is one marked by prayer and sharing, silence and fasting, in anticipation of the joy of Easter.

This year I would like to propose a few thoughts in the light of a brief biblical passage drawn from the Letter to the Hebrews: “Let us be concerned for each other, to stir a response in love and good works.” These words are part of a passage in which the sacred author exhorts us to trust in Jesus Christ as the High Priest who has won us forgiveness and opened up a pathway to God. Embracing Christ bears fruit in a life structured by the three theological virtues: it means approaching the Lord “sincere in heart and filled with faith”, keeping firm “in the hope we profess” and ever mindful of living a life of “love and good works” together with our brothers and sisters. The author states that to sustain this life shaped by the Gospel it is important to participate in the liturgy and community prayer, mindful of the eschatological goal of full communion in God. Here I would like to reflect on verse 24, which offers a succinct, valuable and ever timely teaching on the three aspects of Christian life: concern for others, reciprocity and personal holiness.

1. “Let us be concerned for each other”: responsibility towards our brothers and sisters.

This first aspect is an invitation to be “concerned”: the Greek verb used here is katanoein, which means to scrutinize, to be attentive, to observe carefully and take stock of something. We come across this word in the Gospel when Jesus invites the disciples to “think of” the ravens that, without striving, are at the centre of the solicitous and caring Divine Providence (cf Lk 12:24), and to “observe” the plank in our own eye before looking at the splinter in that of our brother (cf Lk 6:41). In another verse of the Letter to the Hebrews, we find the encouragement to “turn your minds to Jesus” (3:1), the Apostle and High Priest of our faith. So the verb which introduces our exhortation tells us to look at others, first of all at Jesus, to be concerned for one another, and not to remain isolated and indifferent to the fate of our brothers and sisters. All too often, however, our attitude is just the opposite: an indifference and disinterest born of selfishness and masked as a respect for “privacy”. Today too, the Lord’s voice summons all of us to be concerned for one another. Even today God asks us to be “guardians” of our brothers and sisters (Gen 4:9), to establish relationships based on mutual consideration and attentiveness to the well-being, the integral well-being of others. The great commandment of love for one another demands that we acknowledge our responsibility towards those who, like ourselves, are creatures and children of God. Being brothers and sisters in humanity and, in many cases, also in the faith, should help us to recognize in others a true alter ego, infinitely loved by the Lord. If we cultivate this way of seeing others as our brothers and sisters, solidarity, justice, mercy and compassion will naturally well up in our hearts. The Servant of God Pope Paul VI stated that the world today is suffering above all from a lack of brotherhood: “Human society is sorely ill. The cause is not so much the depletion of natural resources, nor their monopolistic control by a privileged few; it is rather the weakening of brotherly ties between individuals and nations” (Populorum Progressio, 66).

Concern for others entails desiring what is good for them from every point of view: physical, moral and spiritual. Contemporary culture seems to have lost the sense of good and evil, yet there is a real need to reaffirm that good does exist and will prevail, because God is “generous and acts generously” (Ps 119:68). The good is whatever gives, protects and promotes life, brotherhood and communion. Responsibility towards others thus means desiring and working for the good of others, in the hope that they too will become receptive to goodness and its demands. Concern for others means being aware of their needs. Sacred Scripture warns us of the danger that our hearts can become hardened by a sort of “spiritual anesthesia” which numbs us to the suffering of others. The Evangelist Luke relates two of Jesus’ parables by way of example. In the parable of the Good Samaritan, the priest and the Levite “pass by”, indifferent to the presence of the man stripped and beaten by the robbers (cf Lk 10:30-32). In that of Dives and Lazarus, the rich man is heedless of the poverty of Lazarus, who is starving to death at his very door (cf Lk 16:19). Both parables show examples of the opposite of “being concerned”, of looking upon others with love and compassion. What hinders this humane and loving gaze towards our brothers and sisters? Often it is the possession of material riches and a sense of sufficiency, but it can also be the tendency to put our own interests and problems above all else. We should never be incapable of “showing mercy” towards those who suffer. Our hearts should never be so wrapped up in our affairs and problems that they fail to hear the cry of the poor. Humbleness of heart and the personal experience of suffering can awaken within us a sense of compassion and empathy. “The upright understands the cause of the weak, the wicked has not the wit to understand it” (Prov 29:7). We can then understand the beatitude of “those who mourn” (Mt 5:5), those who in effect are capable of looking beyond themselves and feeling compassion for the suffering of others. Reaching out to others and opening our hearts to their needs can become an opportunity for salvation and blessedness.

“Being concerned for each other” also entails being concerned for their spiritual well-being. Here I would like to mention an aspect of the Christian life, which I believe has been quite forgotten: fraternal correction in view of eternal salvation. Today, in general, we are very sensitive to the idea of charity and caring about the physical and material well-being of others, but almost completely silent about our spiritual responsibility towards our brothers and sisters. This was not the case in the early Church or in those communities that are truly mature in faith, those which are concerned not only for the physical health of their brothers and sisters, but also for their spiritual health and ultimate destiny. The Scriptures tell us: “Rebuke the wise and he will love you for it. Be open with the wise, he grows wiser still, teach the upright, he will gain yet more” (Prov 9:8ff). Christ himself commands us to admonish a brother who is committing a sin (cf Mt 18:15). The verb used to express fraternal correction - elenchein – is the same used to indicate the prophetic mission of Christians to speak out against a generation indulging in evil (cf Eph 5:11). The Church’s tradition has included “admonishing sinners” among the spiritual works of mercy. It is important to recover this dimension of Christian charity. We must not remain silent before evil. I am thinking of all those Christians who, out of human regard or purely personal convenience, adapt to the prevailing mentality, rather than warning their brothers and sisters against ways of thinking and acting that are contrary to the truth and that do not follow the path of goodness. Christian admonishment, for its part, is never motivated by a spirit of accusation or recrimination. It is always moved by love and mercy, and springs from genuine concern for the good of the other. As the Apostle Paul says: “If one of you is caught doing something wrong, those of you who are spiritual should set that person right in a spirit of gentleness; and watch yourselves that you are not put to the test in the same way” (Gal 6:1). In a world pervaded by individualism, it is essential to rediscover the importance of fraternal correction, so that together we may journey towards holiness. Scripture tells us that even “the upright falls seven times” (Prov 24:16); all of us are weak and imperfect (cf 1 Jn 1:8). It is a great service, then, to help others and allow them to help us, so that we can be open to the whole truth about ourselves, improve our lives and walk more uprightly in the Lord’s ways. There will always be a need for a gaze which loves and admonishes, which knows and understands, which discerns and forgives (cf Lk 22:61), as God has done and continues to do with each of us.

2. “Being concerned for each other”: the gift of reciprocity.

This “custody” of others is in contrast to a mentality that, by reducing life exclusively to its earthly dimension, fails to see it in an eschatological perspective and accepts any moral choice in the name of personal freedom. A society like ours can become blind to physical sufferings and to the spiritual and moral demands of life. This must not be the case in the Christian community! The Apostle Paul encourages us to seek “the ways which lead to peace and the ways in which we can support one another” (Rom 14:19) for our neighbour’s good, “so that we support one another” (15:2), seeking not personal gain but rather “the advantage of everybody else, so that they may be saved” (1 Cor 10:33). This mutual correction and encouragement in a spirit of humility and charity must be part of the life of the Christian community.

The Lord’s disciples, united with him through the Eucharist, live in a fellowship that binds them one to another as members of a single body. This means that the other is part of me, and that his or her life, his or her salvation, concern my own life and salvation. Here we touch upon a profound aspect of communion: our existence is related to that of others, for better or for worse. Both our sins and our acts of love have a social dimension. This reciprocity is seen in the Church, the mystical body of Christ: the community constantly does penance and asks for the forgiveness of the sins of its members, but also unfailingly rejoices in the examples of virtue and charity present in her midst. As Saint Paul says: “Each part should be equally concerned for all the others” (1 Cor 12:25), for we all form one body. Acts of charity towards our brothers and sisters – as expressed by almsgiving, a practice which, together with prayer and fasting, is typical of Lent – is rooted in this common belonging. Christians can also express their membership in the one body which is the Church through concrete concern for the poorest of the poor. Concern for one another likewise means acknowledging the good that the Lord is doing in others and giving thanks for the wonders of grace that Almighty God in his goodness continuously accomplishes in his children. When Christians perceive the Holy Spirit at work in others, they cannot but rejoice and give glory to the heavenly Father (cf Mt 5:16).

3. “To stir a response in love and good works”: walking together in holiness.

These words of the Letter to the Hebrews (10:24) urge us to reflect on the universal call to holiness, the continuing journey of the spiritual life as we aspire to the greater spiritual gifts and to an ever more sublime and fruitful charity (cf 1 Cor 12:31-13:13). Being concerned for one another should spur us to an increasingly effective love which, “like the light of dawn, its brightness growing to the fullness of day” (Prov 4:18), makes us live each day as an anticipation of the eternal day awaiting us in God. The time granted us in this life is precious for discerning and performing good works in the love of God. In this way the Church herself continuously grows towards the full maturity of Christ (cf Eph 4:13). Our exhortation to encourage one another to attain the fullness of love and good works is situated in this dynamic prospect of growth.

Sadly, there is always the temptation to become lukewarm, to quench the Spirit, to refuse to invest the talents we have received, for our own good and for the good of others (cf Mt 25:25ff.). All of us have received spiritual or material riches meant to be used for the fulfilment of God’s plan, for the good of the Church and for our personal salvation (cf Lk 12:21b; 1 Tim 6:18). The spiritual masters remind us that in the life of faith those who do not advance inevitably regress. Dear brothers and sisters, let us accept the invitation, today as timely as ever, to aim for the “high standard of ordinary Christian living” (Novo Millennio Ineunte, 31). The wisdom of the Church in recognizing and proclaiming certain outstanding Christians as Blesseds and as Saints is also meant to inspire others to imitate their virtues. Saint Paul exhorts us to “anticipate one another in showing honour” (Rom 12:10).

In a world which demands of Christians a renewed witness of love and fidelity to the Lord, may all of us feel the urgent need to anticipate one another in charity, service and good works (cf Heb 6:10). This appeal is particularly pressing in this holy season of preparation for Easter. As I offer my prayerful good wishes for a blessed and fruitful Lenten period, I entrust all of you to the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary and from my heart I impart to everyone my Apostolic Blessing.

BENEDICTUS PP. XVI

From the Vatican, 3 November 2011 - © Copyright 2011 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

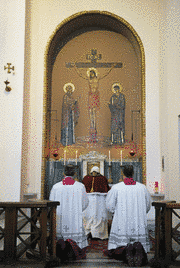

Papa Benedict's Homily at Holy Mass at the Basilica of St Sabina on the Aventine Hill

following a Penitential Procession from the Church of St Anselm - in English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese & Spanish

"Venerable Brothers, Dear Brothers and Sisters

With this day of penance and fasting — Ash Wednesday — we are beginning a new journey to the Resurrection at Easter: the journey of Lent. I would like to reflect briefly on the liturgical symbol of Ashes, a material sign, a natural element, which in the liturgy becomes a sacred symbol, very important on this day which marks the beginning of the Lenten journey. In ancient times, in the Jewish culture, it was common practice to sprinkle ashes on one’s head as a sign of penance, and often also to dress in sack-cloth or rags. Instead, for us Christians this is a special moment which has considerable ritual and spiritual importance.

Firstly, ashes are one of the material signs that bring the cosmos into the Liturgy. The most important signs are those of the Sacraments: water, oil, bread and wine, which become true sacramental elements through which we receive the grace of Christ which comes among us. The ashes are not a sacramental sign, but are nevertheless linked to prayer and the sanctification of the Christian people. In fact, before the distribution of ashes on the heads of each one of us — which we will soon do — they are blessed according to two possible formulas: in the first, they are called “austere symbols”, in the second, we invoke a blessing directly upon them, referring to the text in the Book of Genesis which can also accompany the act of the imposition: “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return” (cf Gen 3:19).

Let us reflect for a moment on this passage of Genesis. It concludes with a judgement God delivered after the original sin. God curses the serpent who caused man and woman to sin. Then he punishes the woman telling her that she will give birth with great pain and will have a biased relationship with her husband. Then he punishes the man, saying he will toil and labour and curses the ground saying “cursed is the ground because of you” (Gen 3:17) because of your sin. Therefore, the man and woman are not cursed directly as the serpent is, but because of Adam’s sin; cursed is the ground from which he was taken. Let us reread the magnificent account of how God created man from the Earth. “Then the Lord God formed man of dust from the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being. And the Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed” (Gen 2:7-8); taken from the Book of Genesis.

Thus the sign of the Ashes recalls the great fresco of creation which tells us that the human being is a singular unity of matter and of the Divine breath, using the image of dust moulded by God and given life by the breath breathed into the nostrils of the new creature. In Genesis, the symbol of dust takes on a negative connotation because of sin. Whereas before the fall the soil was a totally good element, irrigated by spring water (cf Gen 2:6) and through God’s work was capable of producing “every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food” (Gen 2:9), after the fall and the divine curse it was to produce only “thorns and thistles”, and only in exchange for the “toil” and the “sweat of your face” would it bear fruit (cf Gen 3:17-19). The dust of the earth no longer recalls the creative hand of God, one that is open to life, but becomes a sign of an inexorable destiny of death: “You are dust, and to dust you shall return” (Gen 3:19).

It is clear in this Biblical text that the earth participates in man’s destiny. In one of his homilies, St John Chrysostom says: “See how after his disobedience, everything is imposed on man in a way that is contrary to his previous style of life” (Sermones in Genesis 17:9: PG 53, 146). This cursing of the ground has a “medicinal” function for man who learns from the earth’s “resistance” to recognize his limitations and his own human nature. Another ancient commentary summarizes this beautifully, saying: “Adam was created pure by God to serve him. All creatures were created for the service of man. He was destined to be lord and king over all creatures. But when he embraced evil he did so by listening to something outside himself. This penetrated his heart and took over his whole being. Thus ensnared by evil, Creation, which had assisted and served him, was ensnared together with him” (Pseudo-Macarius, Homily 11, 5: PG 34, 547).

As we said earlier, quoting St John Chrysostom, the cursing of the ground has a “medicinal” function: meaning that God’s intention is always good and more profound than the curse. The curse, indeed, does not come from God but from sin. God cannot avoid inflicting it, because he respects man’s freedom and its consequences, even when they are negative. Thus, within the punishment and within the curse of the ground, there is a good intention that comes from God. When he says to man, “You are dust, and to dust you shall return”, together with the just punishment, he also intends to announce the way to salvation, which will pass precisely through the earth, through that “dust”, that “flesh” which will be assumed by the [Incarnate] Word. It is in this salvific perspective that the words of Genesis are repeated in the Ash Wednesday Liturgy: as an invitation to penance, humility, and to have an awareness of our mortal state, not to end in despair, but rather to welcome in this mortal state of ours the unthinkable closeness of God who beyond death, opens the way to resurrection, to paradise finally regained. There is a similar text by Origen that says: “What was initially flesh, from the earth, a man of dust (cf 1 Cor 15:47), and was destroyed by death and returned to dust and ashes — as is written: you are dust, and to dust you shall return — is made to rise again from the earth. Later, according to the merits of the soul that inhabits the body, the person advances towards the glory of a spiritual body” (Sui Prìncipi 3, 6, 5: S.Ch, 268, 248).

The “merits of the soul” of which Origen speaks, are necessary; the merits of Christ, the efficacy of his Paschal Mystery are fundamental. St Paul has summed it for us in the Second Letter to the Corinthians, today’s Second Reading: “For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Cor 5:11). Our possibility of receiving divine forgiveness depends essentially on the fact that God himself, in the person of his Son, wished to share in our human condition, but not in the corruption of sin. The Father raised him through the power of his Holy Spirit and Jesus, the new Adam, became, as St Paul says: “a life-giving spirit” (1 Cor 15:45), the first fruits of the new creation. The same Spirit who raised Jesus from the dead can turn our hearts from hearts of stone into hearts of flesh (cf Ezek 36:26). We invoked him just now in the Psalm Miserere: “Create in me a clean heart, O God, and put a new and right spirit within me. Cast me not away from your presence, and take not your holy Spirit from me” (Ps 51[50]:10, 11). That same God who banished our first parents from Eden, sent his own Son to this earth, devastated by sin, without sparing him, so that we, as prodigal children might return, repentent and redeemed through his mercy, to our true homeland. So may it be for all of us, for all believers, and for all those who humbly recognize their need for salvation. Amen."

BXVI - Wednesday Audience, 22 February 2012 - © Copyright 2012 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Papa Benedetto's Catechesis on Ash Wednesday

- in Croatian, English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese & Spanish

"Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In this catechesis, I would like to reflect briefly upon the season of Lent which begins today with the Ash Wednesday Liturgy. It is a 40-day journey that will bring us to the Easter Triduum — the memorial of the Lord’s Passion, death and Resurrection, the heart of the mystery of our salvation. In the first centuries of the Church’s life this was the time when those who had heard and received the proclamation of Christ set out, step by step, on their journey of faith and conversion in order to receive the sacrament of Baptism. For the catechumens — namely, those who wished to become Christian and to be incorporated into Christ and into the Church — it was a matter of drawing closer to the living God and an initiation to faith which was to take place gradually, through inner transformation.

Subsequently, penitents and then all the faithful were also asked to make this journey of spiritual renewal and increasingly to conform their lives to Christ’s. The participation of the whole community in the various stages of the Lenten journey emphasizes an important dimension of Christian spirituality: Christ’s death and resurrection does not bring the redemption of a few but of all. For this reason everyone, both those who were making a journey of faith as catechumens to receive Baptism and those who had drifted away from God and from the community of faith and were seeking reconciliation, as well as those who were living their faith in full communion with the Church, knew that the season which precedes Easter is a time of metanoia; that is, of a change of heart, of repentance; it is the season that identifies our human life and the whole of history as a process of conversion that starts now, to encounter the Lord at the end of time.

Using an expression that has become characteristic in the liturgy, the Church calls the season we have entered today “Quadragesima”, namely, a 40-day period and, with a clear reference to Sacred Scripture, in this way introduces us into a precise spiritual context. In fact, 40 is the symbolic number with which both the Old and the New Testaments represent the salient moments in the experience of faith of the People of God. It is a number that stands for the time of waiting, of purification, of the return to the Lord, of the knowledge that God keeps his promises. This number does not represent an exact chronological period, marked by the sum of its days. Rather, it suggests patient perseverance, a long trial, a sufficient length of time in which to perceive God’s works, a time within which one must resolve to assume one’s responsibilities with no further postponement. It is the time for mature decisions.

The number 40 first appears in the story of Noah. Because of the flood this righteous man spends 40 days and 40 nights in the Ark, with his family and with the animals that God had told him to take with him. And he waits another 40 days, after the flood, before touching dry land, saved from destruction (cf Gen 7:4,12; 8:6). Then, the next stage: Moses remains in the Lord’s presence on Mount Sinai for 40 days and 40 nights to receive the Law. He fasts throughout this period (cf Ex 24:18). The journey of the Jewish people from Egypt to the Promised Land lasts for 40 years, an appropriate span of time to experience God’s faithfulness. “You shall remember all the way which the Lord your God has led you these forty years in the wilderness … your clothing did not wear out upon you, and your foot did not swell, these forty years”, Moses says in Deuteronomy at the end of the 40 years’ migration (8:2, 4). The years of peace that Israel enjoys under the Judges are 40 (cf 3:11, 30); but once this time has passed, forgetfulness of God’s gifts and the return to sin creep in. The Prophet Elijah takes 40 days to reach Mount Horeb, the mountain where he encounters God (cf 1 Kings 19:8). For 40 days the inhabitants of Ninevah do penance in order to obtain God’s forgiveness (cf Jon 3:4). Forty is also the number of years of the reigns of Saul (cf Acts 13:21), of David (cf 2 Sam 5:4-5) and of Solomon (cf 1 Kings 11:42), the first three kings of Israel. The Psalms also reflect on the biblical significance of the 40 years; for example, Psalm 95[94], a passage of which we have just heard: “O that today you would listen to his voice! Harden not your hearts, as at Meribah, as on the day at Massah in the wilderness, when your fathers put me to the test, when they tried me though they saw my works. For forty years I was wearied of these people and I said, ‘Their hearts are astray, these people do not know my ways’” (vv. 7c-10).

In the New Testament, before beginning his public ministry, Jesus withdraws into the wilderness for 40 days, neither eating nor drinking (cf Mt 4:2); his nourishment is the Word of God, which he uses as a weapon to triumph over the devil. Jesus’ temptations recall those that the Jewish people faced in the desert, but which they were unable to overcome. It is for 40 days that the Risen Jesus instructs his disciples before ascending into heaven and sending the Holy Spirit (cf Acts 1:3).

This recurring number of 40 describes a spiritual context which is still timely and applicable, and the Church, precisely by means of the days of the Lenten season, wishes to preserve their enduring value and show us their effectiveness. The purpose of the Christian liturgy of Lent is to encourage a journey of spiritual renewal in the light of this long biblical experience and, especially, to learn to imitate Jesus, who by spending 40 days in the wilderness taught how to overcome temptation with the word of God. The 40 years that Israel spent wandering through the wilderness reveal ambivalent attitudes and situations. On the one hand they are the season of the first love with God and between God and his people, when he speaks to their hearts, continuously pointing out to them the path to follow. God had, as it were, made his dwelling place in Israel’s midst, he went before his people in a cloud or in a pillar of fire; he provided food for them every day by bringing down manna from heaven and making water flow from the rock. The years that Israel spent in the wilderness can thus be seen as the time of God’s predilection, the time when the People adhered to him: a time of first love. On the other hand, the Bible also shows another image of Israel’s wanderings in the wilderness: the time of the greatest temptations and dangers too, when Israel mutters against its God and, feeling the need to worship a God who is closer and more tangible, would like to return to paganism and build its own idols. It is also the time of rebellion against the great and invisible God.

In Jesus’ earthly pilgrimage we are surprised to discover this ambivalence, a time of special closeness to God — a time of first love — and a time of temptation — the temptation to return to paganism, but of course without any compromise with sin. After his Baptism of penance in the Jordan, when he takes upon himself the destiny of the Servant of God who renounces himself, lives for others and puts himself among sinners to take the sin of the world upon himself, Jesus goes into the wilderness and remains there for 40 days in profound union with the Father, thereby repeating Israel’s history, with all those cadences of 40 days or years which I have mentioned. This dynamic is a constant in the earthly life of Jesus, who always seeks moments of solitude in order to pray to his Father and to remain in intimate communion, in intimate solitude with him, in an exclusive communion with him, and then to return to the people. However in this period of “wilderness” and of his special encounter with the Father, Jesus is exposed to danger and is assaulted by the temptation and seduction of the Evil One, who proposes a different messianic path to him, far from God’s plan because it passes through power, success and domination rather than the total gift of himself on the Cross. This is the alternative: a messianism of power, of success, or a messianism of love, of the gift of self.

This situation of ambivalence also describes the condition of the Church journeying through the “wilderness” of the world and of history. In this “desert” we believers certainly have the opportunity for a profound experience of God who strengthens the spirit, confirms faith, nourishes hope and awakens charity; an experience that enables us to share in Christ’s victory over sin and death through his sacrifice of love on the Cross. However the “wilderness” is also a negative aspect of the reality that surrounds us: aridity, the poverty of words of life and of values, secularism and cultural materialism, which shut people into the worldly horizons of existence, removing them from all reference to transcendence. This is also the environment in which the sky above us is dark, because it is covered with the clouds of selfishness, misunderstanding and deceit. In spite of this, for the Church today the time spent in the wilderness may be turned into a time of grace, for we have the certainty that God can make the living water that quenches thirst and brings refreshment gush from even the hardest rock.

Dear brothers and sisters, in these 40 days that will bring us to the Resurrection at Easter, we can find fresh courage for accepting with patience and faith every situation of difficulty, affliction and trial in the knowledge that from the darkness the Lord will cause a new day to dawn. And if we are faithful to Jesus, following him on the Way of the Cross, the clear world of God, the world of light, truth and joy will be, as it were, restored to us. It will be the new dawn, created by God himself. A good Lenten journey to you all!"

BXVI - Wednesday Audience, 22 February 2012 - © Copyright 2012 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana