Dominum et Vivificantem

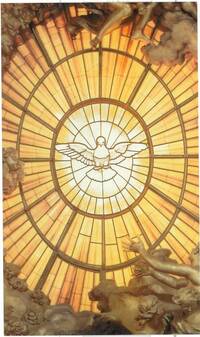

Pope St John Paul II gave us this encyclical on the Holy Spirit on the Solemnity of Pentecost, 18th May 1986.

Extracts from this encyclical have been read on a Totus2us Novena. The music (Veni Sancte Spiritus) is sung by the Poor Clare Sisters in enclosed community at Ty Mam Duw (North Wales). To download the free mp3 audio recordings individually, double/right click on the blue play buttons.

Pope St John Paul II's Encyclical Letter

on

the Holy Spirit

in the Life of the Church and the World

also in French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Latin, Polish, Portuguese & Spanish

INTRODUCTION

Venerable Brothers, Beloved Sons and Daughters,

Health and the Apostolic Blessing!

1. The Church professes her faith in the Holy Spirit as "the Lord, the giver of life". She professes this in the Creed which is called Nicene-Constantinopolitan from the name of the two Councils - of Nicaea (325 AD) and Constantinople (381 AD) - at which it was formulated or promulgated. It also contains the statement that the Holy Spirit "has spoken through the Prophets".

These are words which the Church receives from the very source of her faith, Jesus Christ. In fact, according to the Gospel of John, the Holy Spirit is given to us with the new life, as Jesus foretells and promises on the great day of the Feast of Tabernacles: "If any one thirst let him come to me and drink. He who believeth in me as the scripture has said, 'Out of his heart shall flow rivers of living water'" (Jn 7, 37). And the Evangelist explains: "This he said about the Spirit, which those who believed in him were to receive" (Jn 7, 39). It is the same simile of water which Jesus uses in his conversation with the Samaritan woman, when he speaks of "a spring of water welling up to eternal life," (Jn 4, 14; cf Lumen Gentium, 4) and in his conversation with Nicodemus when he speaks of the need for a new birth "of water and the Holy Spirit" in order to "enter the kingdom of God" (cf Jn 3, 5).

The Church, therefore, instructed by the words of Christ, and drawing on the experience of Pentecost and her own apostolic history, has proclaimed since the earliest centuries her faith in the Holy Spirit, as the giver of life, the one in whom the inscrutable Triune God communicates himself to human beings, constituting in them the source of eternal life.

2. This faith, uninterruptedly professed by the Church, needs to be constantly reawakened and deepened in the consciousness of the People of God. In the course of the last hundred years this has been done several times: by Leo XIII, who published the encyclical epistle Divinum Illud Munus (1897) entirely devoted to the Holy Spirit; by Pius XII, who in the encyclical letter Mystici Corporis (1943) spoke of the Holy Spirit as the vital principle of the Church, in which he works in union with the Head of the Mystical Body, Christ; at the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council which brought out the need for a new study of the doctrine on the Holy Spirit, as Paul VI emphasized: "The Christology and particularly the ecclesiology of the Council must be succeeded by a new study of and devotion to the Holy Spirit, precisely as the indispensable complement to the teaching of the Council" (General Audience, 6 June 1973).

In our own age, then, we are called anew by the ever ancient and ever new faith of the Church, to draw near to the Holy Spirit as the giver of life. In this we are helped and stimulated also by the heritage we share with the Oriental Churches, which have jealously guarded the extraordinary riches of the teachings of the Fathers on the Holy Spirit. For this reason too we can say that one of the most important ecclesial events of recent years has been the XVIth centenary of the First Council of Constantinople, celebrated simultaneously in Constantinople and Rome on the Solemnity of Pentecost 1981. The Holy Spirit was then better seen, through a meditation on the mystery of the Church, as the one who points out the ways leading to the union of Christians, indeed as the supreme source of this unity, which comes from God himself and to which St Paul gave a particular expression in the words which are frequently used to begin the Eucharistic liturgy: "The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all" (Roman Missal; cf 2 Cor 13, 13).

In a certain sense, my previous encyclicals Redemptor Hominis and Dives in Misericordia took their origin and inspiration from this exhortation, celebrating as they do the event of our salvation accomplished in the Son, sent by the Father into the world "that the world might be saved through him" (Jn 3, 17) and "every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father" (Phil 2, 11). From this exhortation now comes the present encyclical on the Holy Spirit, who proceeds from the Father and the Son; with the Father and the Son he is adored and glorified: a divine Person, he is at the center of the Christian faith and is the source and dynamic power of the Church's renewal (cf LG, 4; JPII, Address to International Congress on Pneumatology 26 March 1982). The encyclical has been drawn from the heart of the heritage of the Council. For the Conciliar texts, thanks to their teaching on the Church in herself and the Church in the world, move us to penetrate ever deeper into the Trinitarian mystery of God himself, through the Gospels, the Fathers and the liturgy: to the Father, through Christ, in the Holy Spirit.

In this way the Church is also responding to certain deep desires which she believes she can discern in people's hearts today: a fresh discovery of God in his transcendent reality as the infinite Spirit, just as Jesus presents him to the Samaritan woman; the need to adore him "in spirit and truth" (cf Jn 4, 24); the hope of finding in him the secret of love and the power of a "new creation" (cf Rom 8, 22; Gal 6, 15): yes, precisely the giver of life.

The Church feels herself called to this mission of proclaiming the Spirit, while together with the human family she approaches the end of the second Millennium after Christ. Against the background of a heaven and earth which will "pass away," she knows well that "the words which will not pass away" (cf Mt 24, 35) acquire a particular eloquence. They are the words of Christ about the Holy Spirit, the inexhaustible source of the "water welling up to eternal life," (Jn 4, 14) as truth and saving grace. Upon these words she wishes to reflect, to these words she wishes to call the attention of believers and of all people, as she prepares to celebrate - as will be said later on - the great Jubilee which will mark the passage from the second to the third Christian Millennium.

Naturally, the considerations that follow do not aim to explore exhaustively the extremely rich doctrine on the Holy Spirit, nor to favour any particular solution of questions which are still open. Their main purpose is to develop in the Church the awareness that "she is compelled by the Holy Spirit to do her part towards the full realization of the will of God, who has established Christ as the source of salvation for the whole world" (LG, 17).

PART I - THE SPIRIT OF THE FATHER AND OF THE SON, GIVEN TO THE CHURCH

I Jesus' Promise and Revelation at the Last Supper

3. When the time for Jesus to leave this world had almost come, he told the Apostles of "another Counselor" (Allon parakleton: Jn 14, 16). The evangelist John, who was present, writes that, during the Last Supper before the day of his Passion and Death, Jesus addressed the Apostles with these words: "Whatever you ask in my name, I will do it, that the Father may be glorified in the Son.... I will pray the Father, and he will give you another Counselor, to be with you forever, even the Spirit of truth" (Jn 14, 13,16f).

It is precisely this Spirit of truth whom Jesus calls the Paraclete - and parakletos means "counselor," and also "intercessor," or "advocate." And he says that the Paraclete is "another" Counselor, the second one, since he, Jesus himself, is the first Counselor (cf 1 Jn 2, 1), being the first bearer and giver of the Good News. The Holy Spirit comes after him and because of him, in order to continue in the world, through the Church, the work of the Good News of salvation. Concerning this continuation of his own work by the Holy Spirit Jesus speaks more than once during the same farewell discourse, preparing the Apostles gathered in the Upper Room for his departure, namely for his Passion and Death on the Cross.

The words to which we will make reference here are found in the Gospel of John. Each one adds a new element to that prediction and promise. And at the same time they are intimately interwoven, not only from the viewpoint of the events themselves but also from the viewpoint of the mystery of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, which perhaps in no passage of Sacred Scripture finds so emphatic an expression as here.

4. A little while after the prediction just mentioned Jesus adds: "But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you" (Jn 14, 26). The Holy Spirit will be the Counselor of the Apostles and the Church, always present in their midst - even though invisible - as the teacher of the same Good News that Christ proclaimed. The words "he will teach" and "bring to remembrance" mean not only that he, in his own particular way, will continue to inspire the spreading of the Gospel of salvation but also that he will help people to understand the correct meaning of the content of Christ's message; they mean that he will ensure continuity and identity of understanding in the midst of changing conditions and circumstances. The Holy Spirit, then, will ensure that in the Church there will always continue the same truth which the Apostles heard from their Master.

5. In transmitting the Good News, the Apostles will be in a special way associated with the Holy Spirit. This is how Jesus goes on: "When the Counselor comes, whom I shall send to you from the Father, even the Spirit of truth, who proceeds from the Father, he will bear witness to me; and you also are witnesses, because you have been with me from the beginning" (Jn 15, 26f).

Apostles were the direct eyewitnesses. They "have heard" and "have seen with their own eyes," "have looked upon" and even "touched with their hands" Christ, as the evangelist John says in another passage (cf 1 Jn 1, 1-3; 4, 14). This human, first-hand and "historical" witness to Christ is linked to the witness of the Holy Spirit: "He will bear witness to me." In the witness of the Spirit of truth, the human testimony of the Apostles will find its strongest support. And subsequently it will also find therein the hidden foundation of its continuation among the generations of Christ's disciples and believers who succeed one another down through the ages.

The supreme and most complete revelation of God to humanity is Jesus Christ himself, and the witness of the Spirit inspires, guarantees and convalidates the faithful transmission of this revelation in the preaching and writing of the Apostles (Dei Verbum, 11, 12), while the witness of the Apostles ensures its human expression in the Church and in the history of humanity.

6. This is also seen from the strict correlation of content and intention with the just-mentioned prediction and promise, a correlation found in the next words of the text of John: "I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth; for he will not speak on his own authority, but whatever he hears he will speak, and he will declare to you the things that are to come" (Jn 16, 12f).

In his previous words Jesus presents the Counselor, the Spirit of truth, as the one who "will teach" and "bring to remembrance," as the one who "will bear witness" to him. Now he says: "He will guide you into all the truth." This "guiding into all the truth," referring to what the Apostles "cannot bear now", is necessarily connected with Christ's self-emptying through his Passion and Death on the Cross which, when he spoke these words, was just about to happen.

Later however it becomes clear that this "guiding into all the truth" is connected not only with the scandal of the Cross, but also with everything that Christ "did and taught" (Acts 1, 1). For the mystery of Christ taken as a whole demands faith, since it is faith that adequately introduces man into the reality of the revealed mystery. The "guiding into all the truth" is therefore achieved in faith and through faith: and this is the work of the Spirit of truth and the result of his action in man. Here the Holy Spirit is to be man's supreme guide and the light of the human spirit. This holds true for the Apostles, the eyewitnesses, who must now bring to all people the proclamation of what Christ did and taught, and especially the proclamation of his Cross and Resurrection. Taking a longer view, this also holds true for all the generations of disciples and confessors of the Master. Since they will have to accept with faith and confess with candour the mystery of God at work in human history, the revealed mystery which explains the definitive meaning of that history.

7. Between the Holy Spirit and Christ there thus subsists, in the economy of salvation, an intimate bond, whereby the Spirit works in human history as "another Counselor", permanently ensuring the transmission and spreading of the Good News revealed by Jesus of Nazareth. Thus, in the Holy Spirit-Paraclete, who in the mystery and action of the Church unceasingly continues the historical presence on earth of the Redeemer and his saving work, the glory of Christ shines forth, as the following words of John attest: "He [the Spirit of truth] will glorify me, for he will take what is mine and declare it to you" (Jn 16, 14). By these words all the preceding statements are once again confirmed: "He will teach .., will bring to your remembrance .., will bear witness." The supreme and complete self-revelation of God, accomplished in Christ and witnessed to by the preaching of the Apostles, continues to be manifested in the Church through the mission of the invisible Counselor, the Spirit of truth. How intimately this mission is linked with the mission of Christ, how fully it draws from this mission of Christ, consolidating and developing in history its salvific results, is expressed by the verb "take": "He will take what is mine and declare it to you." As if to explain the words "he will take" by clearly expressing the divine and Trinitarian unity of the source, Jesus adds: "All that the Father has is mine; therefore I said that he will take what is mine and declare it to you" (Jn 16, 15). By the very fact of taking what is "mine," he will draw from "what is the Father's."

In the light of these words "he will take," one can therefore also explain the other significant words about the Holy Spirit spoken by Jesus in the Upper Room before the Passover: "It is to your advantage that I go away, for if I do not go away, the Counselor will not come to you; but if I go, I will send him to you. And when he comes, he will convince the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgment" (Jn 16, 7f). It will be necessary to return to these words in a separate reflection.

II Father, Son and Holy Spirit

8. It is a characteristic of the text of John that the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit are clearly called Persons, the first distinct from the second and the third, and each of them from one another. Jesus speaks of the Spirit-Counselor, using several times the personal pronoun "he"; and at the same time, throughout the farewell discourse, he reveals the bonds which unite the Father, the Son and the Paraclete to one another. Thus "the Holy Spirit . . .proceeds from the Father" (Jn 15, 26) and the Father "gives" the Spirit (Jn 14, 16). The Father "sends" the Spirit in the name of the Son (Jn 14, 26), the Spirit "bears witness" to the Son (Jn 15, 26). The Son asks the Father to send the Spirit-Counselor (Jn 14, 16), but likewise affirms and promises, in relation to his own "departure" through the Cross: "If I go, I will send him to you" (Jn 16, 7). Thus the Father sends the Holy Spirit in the power of his Fatherhood, as he has sent the Son (cf Jn 3, 16f,34; 6, 57; 17, 3,18,23); but at the same time he sends him in the power of the Redemption accomplished by Christ - and in this sense Holy Spirit is sent also by the Son: "I will send him to you."

Here it should be noted that, while all the other promises made in the Upper Room foretold the coming of the Holy Spirit after Christ's departure, the one contained in the text of John 16, 7f also includes and clearly emphasizes the relationship of interdependence which could be called causal between the manifestation of each: "If I go, I will send him to you." The Holy Spirit will come insofar as Christ will depart through the Cross: he will come not only afterwards, but because of the Redemption accomplished by Christ, through the will and action of the Father.

9. Thus in the farewell discourse at the Last Supper, we can say that the highest point of the revelation of the Trinity is reached. At the same time, we are on the threshold of definitive events and final words which in the end will be translated into the great missionary mandate addressed to the Apostles and through them to the Church: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations", a mandate which contains, in a certain sense, the Trinitarian formula of baptism: "baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (Mt 28, 19). The formula reflects the intimate mystery of God, of the divine life, which is the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, the divine unity of the Trinity. The farewell discourse can be read as a special preparation for this Trinitarian formula, in which is expressed the life-giving power of the Sacrament which brings about sharing in the life of the Triune God, for it gives sanctifying grace as a supernatural gift to man. Through grace, man is called and made "capable" of sharing in the inscrutable life of God.

10. In his intimate life, God "is love" (cf 1 Jn 4, 8,16), the essential love shared by the three divine Persons: personal love is the Holy Spirit as the Spirit of the Father and the Son. Therefore he "searches even the depths of God" (cf I Cor 2, 10), as uncreated Love-Gift. It can be said that in the Holy Spirit the intimate life of the Triune God becomes totally gift, an exchange of mutual love between the divine Persons and that through the Holy Spirit God exists in the mode of gift. It is the Holy Spirit who is the personal expression of this self-giving, of this being-love (cf Aquinas, Summa Theo. Ia, q 37-38). He is Person-Love. He is Person-Gift. Here we have an inexhaustible treasure of the reality and an inexpressible deepening of the concept of person in God, which only divine Revelation makes known to us.

At the same time, the Holy Spirit, being consubstantial with the Father and the Son in divinity, is love and uncreated gift from which derives as from its source (fons vivus) all giving of gifts vis-a-vis creatures (created gift): the gift of existence to all things through creation; the gift of grace to human beings through the whole economy of salvation. As the Apostle Paul writes: "God's love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit which has been given to us" (Rom 5, 5).

III The Salvific Self-Giving of God in the Holy Spirit

11. Christ's farewell discourse at the Last Supper stands in particular reference to this "giving" and "self-giving" of the Holy Spirit. In John's Gospel we have as it were the revelation of the most profound "logic" of the saving mystery contained in God's eternal plan, as an extension of the ineffable communion of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. This is the divine "logic" which from the mystery of the Trinity leads to the mystery of the Redemption of the world in Jesus Christ. The Redemption accomplished by the Son in the dimensions of the earthly history of humanity - accomplished in his "departure" through the Cross and Resurrection - is at the same time, in its entire salvific power, transmitted to the Holy Spirit: the one who "will take what is mine" (Jn 16, 14). The words of the text of John indicate that, according to the divine plan, Christ's "departure" is an indispensable condition for the "sending" and the coming of the Holy Spirit, but these words also say that what begins now is the new salvific self-giving of God, in the Holy Spirit.

12. It is a new beginning in relation to the first, original beginning of God's salvific self-giving, which is identified with the mystery of creation itself. Here is what we read in the very first words of the Book of Genesis: "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth..., and the Spirit of God (ruah Elohim) was moving over the face of the waters" (Gen 1, 1). This biblical concept of creation includes not only the call to existence of the very being of the cosmos, that is to say the giving of existence, but also the presence of the Spirit of God in creation, that is to say the beginning of God's salvific self-communication to the things he creates. This is true first of all concerning man, who has been created in the image and likeness of God: "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness" (Gen 1, 26). "Let us make": can one hold that the plural which the Creator uses here in speaking of himself already in some way suggests the Trinitarian mystery, the presence of the Trinity in the work of the creation of man? The Christian reader, who already knows the revelation of this mystery, can discern a reflection of it also in these words. At any rate, the context of the Book of Genesis enables us to see in the creation of man the first beginning of God's salvific self-giving commensurate with the "image and likeness" of himself which he has granted to man.

13. It seems then that even the words spoken by Jesus in the farewell discourse should be read again in the light of that "beginning", so long ago yet fundamental, which we know from Genesis. "If I do not go away, the Counselor will not come to you; but if I go, I will send him to you." Describing his "departure" as a condition for the "coming" of the Counselor, Christ links the new beginning of God's salvific self-communication in the Holy Spirit with the mystery of the Redemption. It is a new beginning, first of all because between the first beginning and the whole of human history - from the original fall onwards - sin has intervened, sin which is in contradiction to the presence of the Spirit of God in creation, and which is above all in contradiction to God's salvific self-communication to man. St Paul writes that, precisely because of sin, "creation...was subjected to futility .., has been groaning in travail together until now" and "waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God" (Rom 8, 19-22).

14. Therefore Jesus Christ says in the Upper Room "It is to your advantage I go away; ...if I go, I will send him to you" (Jn 16, 7). The "departure" of Christ through the Cross has the power of the Redemption - and this also means a new presence of the Spirit of God in creation: the new beginning of God's self-communication to man in the Holy Spirit. "And that you are children is proven by the fact that God has sent into our hearts the Spirit of his Son who cries: Abba, Father!" As the Apostle Paul writes in the Letter to the Galatians (Gal 4, 6; cf Rom 8, 15). The Holy Spirit is the Spirit of the Father, as the words of the farewell discourse in the Upper Room bear witness. At the same time he is the Spirit of the Son: he is the Spirit of Jesus Christ, as the Apostles and particularly Paul of Tarsus will testify (cf Gal 4, 6; Phil 1, 19; Rom 8, 11). With the sending of this Spirit "into our hearts," there begins the fulfillment of that for which "creation waits with eager longing," as we read in the Letter to the Romans.

The Holy Spirit comes at the price of Christ's "departure." While this "departure" caused the Apostles to be sorrowful (cf Jn 16, 6), and this sorrow was to reach its culmination in the Passion and Death on Good Friday, "this sorrow will turn into joy" (cf Jn 16, 20). For Christ will add to this redemptive "departure" the glory of his Resurrection and Ascension to the Father. Thus the sorrow with its underlying joy is, for the Apostles in the context of their Master's "departure," an "advantageous" departure, for thanks to it another "Counselor" will come (cf Jn 16, 7). At the price of the Cross which brings about the Redemption, in the power of the whole Paschal Mystery of Jesus Christ, the Holy Spirit comes in order to remain from the day of Pentecost onwards with the Apostles, to remain with the Church and in the Church, and through her in the world.

In this way there is definitively brought about that new beginning of the self-communication of the Triune God in the Holy Spirit through the work of Jesus Christ, the Redeemer of man and of the world.

IV The Messiah, Anointed with the Holy Spirit

15. There is also accomplished in its entirety the mission of the Messiah, that is to say of the One who has received the fullness of the Holy Spirit for the Chosen People of God and for the whole of humanity. "Messiah" literally means "Christ", that is, "Anointed One", and in the history of salvation it means "the one anointed with the Holy Spirit". This was the prophetic tradition of the Old Testament. Following this tradition, Simon Peter will say in the house of Cornelius: "You must have heard about the recent happenings in Judea...after the baptism which John preached: how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power" (Acts 10, 37f).

From these words of Peter and from many similar ones (cf Lk 4, 16-21; 3, 16; 4, 14; Mk 1, 10), one must first go back to the prophecy of Isaiah, sometimes called "the Fifth Gospel" or "the Gospel of the Old Testament." Alluding to the coming of a mysterious personage, which the New Testament revelation will identify with Jesus, Isaiah connects his person and mission with a particular action of the Spirit of God - the Spirit of the Lord. These are the words of the Prophet:

"There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse,

and a branch shall grow out of his roots.

And the Spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him,

the spirit of wisdom and understanding,

the spirit of counsel and might,

the spirit of knowledge and the fear of the Lord.

And his delight shall be the fear of the Lord" (Is 11, 1-3).

This text is important for the whole pneumatology of the Old Testament, because it constitutes a kind of bridge between the ancient biblical concept of "spirit", understood primarily as a "charismatic breath of wind", and the "Spirit" as a person and as a gift, a gift for the person. The Messiah of the lineage of David ("from the stump of Jesse") is precisely that person upon whom the Spirit of the Lord "shall rest". It is obvious that in this case one cannot yet speak of a revelation of the Paraclete. However, with this veiled reference to the figure of the future Messiah there begins, so to speak, the path towards the full revelation of the Holy Spirit in the unity of the Trinitarian mystery, a mystery which will finally be manifested in the New Covenant.

16. It is precisely the Messiah himself who is this path. In the Old Covenant, anointing had become the external symbol of the gift of the Spirit. The Messiah (more than any other anointed personage in the Old Covenant) is that single great personage anointed by God himself. He is the Anointed One in the sense that he possesses the fullness of the Spirit of God. He himself will also be the mediator in granting this Spirit to the whole People. Here in fact are other words of the Prophet:

"The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me,

because the Lord has anointed me to bring good tidings to the afflicted;

he has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted

to proclaim liberty to the captives,

and the opening of the prison to those who are bound;

to proclaim the year of the Lord's favour" (Is 61, 1f).

The Anointed One is also sent "with the Spirit of the Lord":

"Now the Lord God has sent me and his Spirit" (Is 48, 16).

According to the Book of Isaiah, the Anointed One and the One sent together with the Spirit of the Lord is also the chosen Servant of the Lord upon whom the Spirit of God comes down:

"Behold my servant, whom I uphold,

my chosen, in whom my soul delights;

I have put my Spirit upon him" (Is 42, 1).

We know that the Servant of the Lord is revealed in the Book of Isaiah as the true Man of Sorrows: the Messiah who suffers for the sins of the world (cf Is 53, 5-6,8). And at the same time it is precisely he whose mission will bear for all humanity the true fruits of salvation:

"He will bring forth justice to the nations ..." (Is 42, 1); and he will become "a covenant to the people, a light to the nations ..." (Is 42, 6); "that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth" (Is 49, 6).

For: "My spirit which is upon you, and my words which I have put in your mouth, shall not depart out of your mouth, or out of the mouth of your children's children, says the Lord, from this time forth and for evermore" (Is 59, 21).

The prophetic texts quoted here are to be read in the light of the Gospel - just as, in its turn, the New Testament draws a particular clarification from the marvelous light contained in these Old Testament texts. The Prophet presents the Messiah as the one who comes in the Holy Spirit, the one who possesses the fullness of this Spirit in himself and at the same time for others, for Israel, for all the nations, for all humanity. The fullness of the Spirit of God is accompanied by many different gifts, the treasures of salvation, destined in a particular way for the poor and suffering, for all those who open their hearts to these gifts - sometimes through the painful experience of their own existence - but first of all through that interior availability which comes from faith. The aged Simeon, the "righteous and devout man" upon whom "rested the Holy Spirit," sensed this at the moment of Jesus' presentation in the Temple, when he perceived in him the "salvation... prepared in the presence of all peoples" at the price of the great suffering - the Cross - which he would have to embrace together with his Mother (cf Lk 2, 25-35). The Virgin Mary, who "had conceived by the Holy Spirit," (cf Lk 1, 35) sensed this even more clearly, when she pondered in her heart the "mysteries" of the Messiah, with whom she was associated (cf Lk 2, 19,51).

17. Here it must be emphasized that clearly the "spirit of the Lord" who rests upon the future Messiah is above all a gift of God for the person of that Servant of the Lord. But the latter is not an isolated and independent person, because he acts in accordance with the will of the Lord, by virtue of the Lord's decision or choice. Even though in the light of the texts of Isaiah the salvific work of the Messiah, the Servant of the Lord, includes the action of the Spirit which is carried out through himself, nevertheless in the Old Testament context there is no suggestion of a distinction of subjects, or of the Divine Persons as they subsist in the mystery of the Trinity, and as they are later revealed in the New Testament. Both in Isaiah and in the whole of the Old Testament the personality of the Holy Spirit is completely hidden: in the revelation of the one God, as also in the foretelling of the future Messiah.

18. Jesus Christ will make reference to this prediction contained in the words of Isaiah at the beginning of his messianic activity. This will happen in the same Nazareth where he had lived for thirty years in the house of Joseph the carpenter, with Mary, his Virgin Mother. When he had occasion to speak in the Synagogue, he opened the Book of Isaiah and found the passage where it was written: "The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me"; and having read this passage he said to those present: "Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing" (cf Lk 4, 16-21; Is 61, 1). In this way he confessed and proclaimed that he was the Messiah, the one in whom the Holy Spirit dwells as the gift of God himself, the one who possesses the fullness of this Spirit, the one who marks the "new beginning" of the gift which God makes to humanity in the Spirit.

5. Jesus of Nazareth, "Exalted" in the Holy Spirit

19. Even though in his hometown of Nazareth Jesus is not accepted as the Messiah, nonetheless, at the beginning of his public activity, his messianic mission in the Holy Spirit is revealed to the people by John the Baptist. The latter, the son of Zechariah and Elizabeth, foretells at the Jordan the coming of the Messiah and administers the baptism of repentance. He says: "I baptize you with water; he who is mightier than I is coming, the thong of whose sandals I am not worthy to untie; he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire" (Lk 3, 16; cf Mt 3, 11; Mk 1, 7; Jn 1, 33). John the Baptist foretells the Messiah - Christ not only as the one who "is coming" in the Holy Spirit but also as the one who "brings" the Holy Spirit, as Jesus will reveal more clearly in the Upper Room. Here John faithfully echoes the words of Isaiah, words which in the ancient Prophet concerned the future, while in John's teaching on the banks of the Jordan they are the immediate introduction to the new messianic reality. John is not only a prophet but also a messenger: he is the precursor of Christ. What he foretells is accomplished before the eyes of all. Jesus of Nazareth too comes to the Jordan to receive the baptism of repentance. At the sight of him arriving, John proclaims: "Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world" (Jn 1, 29). He says this through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit (cf Jn 1, 33f), bearing witness to the fulfillment of the prophecy of Isaiah. At the same time he confesses his faith in the redeeming mission of Jesus of Nazareth. On the lips of John the Baptist, "Lamb of God" is an expression of truth about the Redeemer no less significant than the one used by Isaiah: "Servant of the Lord."

Thus, by the testimony of John at the Jordan, Jesus of Nazareth, rejected by his own fellow-citizens, is exalted before the eyes of Israel as the Messiah, that is to say the "One Anointed" with the Holy Spirit. And this testimony is corroborated by another testimony of a higher order, mentioned by the three Synoptics. For when all the people were baptized and as Jesus, having received baptism, was praying, "the heaven was opened, and the Holy Spirit descended upon him in bodily form, as a dove" (Lk 3, 21f; cf Mt 3, 16; Mk 1, 10) and at the same time "a voice from heaven said 'This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased'" (Mt 3, 17).

This is a Trinitarian theophany which bears witness to the exaltation of Christ on the occasion of his baptism in the Jordan. It not only confirms the testimony of John the Baptist but also reveals another more profound dimension of the truth about Jesus of Nazareth as Messiah. It is this: the Messiah is the beloved Son of the Father. His solemn exaltation cannot be reduced to the messianic mission of the "Servant of the Lord". In the light of the theophany at the Jordan, this exaltation touches the mystery of the very person of the Messiah. He has been raised up because he is the beloved Son in whom God is well pleased. The voice from on high says: "my Son".

20. The theophany at the Jordan clarifies only in a fleeting way the mystery of Jesus of Nazareth, whose entire activity will be carried out in the active presence of the Holy Spirit (cf St Basil, De Spiritu Sancto XVI). This mystery would be gradually revealed and confirmed by Jesus himself by means of everything that he "did and taught" (Acts 1, 1). In the course of this teaching and of the messianic signs which Jesus performed before he came to the farewell discourse in the Upper Room, we find events and words which constitute particularly important stages of this progressive revelation. Thus the evangelist Luke, who has already presented Jesus as "full of the Holy Spirit" and "led by the Spirit...in the wilderness" (cf Lk 4, 1), tells us that, after the return of the 72 disciples from the mission entrusted to them by the Master (cf Lk 10, 17-20), while they were joyfully recounting the fruits of their labours, "in that same hour Jesus rejoiced in the Holy Spirit and said: 'I thank you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, that you have hidden these things from the wise and understanding and revealed them to babes; yea, Father, for such was your gracious will'" (Lk 10, 21; cf Mt 11, 25). Jesus rejoices at the fatherhood of God: he rejoices because it has been given to him to reveal this fatherhood; he rejoices, finally, as at a particular outpouring of this divine fatherhood on the "little ones." And the evangelist describes all this as "rejoicing in the Holy Spirit".

This "rejoicing" in a certain sense prompts Jesus to say still more. We hear: "All things have been delivered to me by my Father; and no one knows who the Son is except the Father, or who the Father is except the Son and those to whom the Son chooses to reveal him" (Lk 10, 22; cf Mt 11, 27).

21. That which during the theophany at the Jordan came so to speak "from outside," from on high, here comes "from within", that is to say from the depths of who Jesus is. It is another revelation of the Father and the Son, united in the Holy Spirit. Jesus speaks only of the fatherhood of God and of his own sonship - he does not speak directly of the Spirit, who is Love and thereby the union of the Father and the Son. Nonetheless what he says of the Father and of himself - the Son - flows from that fullness of the Spirit which is in him, which fills his heart, pervades his own "I", inspires and enlivens his action from the depths. Hence that "rejoicing in the Holy Spirit". The union of Christ with the Holy Spirit, a union of which he is perfectly aware, is expressed in that "rejoicing", which in a certain way renders "perceptible" its hidden source. Thus there is a particular manifestation and rejoicing which is proper to the Son of Man, the Christ-Messiah, whose humanity belongs to the person of the Son of God, substantially one with the Holy Spirit in divinity.

In the magnificent confession of the fatherhood of God, Jesus of Nazareth also manifests himself, his divine "I"- for he is the Son "of the same substance" and therefore "no one knows who the Son is except the Father, or who the Father is except the Son," that Son who "for us and for our salvation" became man by the power of the Holy Spirit and was born of a virgin whose name was Mary.

6. The Risen Christ Says: "Receive the Holy Spirit"

22. It is thanks to Luke's narrative that we are brought closest to the truth contained in the discourse in the Upper Room. Jesus of Nazareth, "raised up" in the Holy Spirit, during this discourse and conversation presents himself as the one who brings the Spirit, as the one who is to bring him and "give" him to the Apostles and to the Church at the price of his own "departure" through the Cross.

The verb "bring" is here used to mean first of all "reveal". In the Old Testament, from the Book of Genesis onwards, the Spirit of God was in some way made known, in the first place as a "breath" of God which gives life, as a supernatural "living breath". In the Book of Isaiah, he is presented as a "gift" for the person of the Messiah, as the one who comes down and rests upon him, in order to guide from within all the salvific activity of the "Anointed One". At the Jordan, Isaiah's proclamation is given a concrete form: Jesus of Nazareth is the one who comes in the Holy Spirit and who brings the Spirit as the gift proper to his own Person, in order to distribute that gift by means of this humanity: "He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit" (Mt 3, 11; Lk 3, 16). In the Gospel of Luke, this revelation of the Holy Spirit is confirmed and added to, as the intimate source of the life and messianic activity of Jesus Christ. In the light of what Jesus says in the farewell discourse in the Upper Room, the Holy Spirit is revealed in a new and fuller way. He is not only the gift to the person (the person of the Messiah), but is a Person-gift. Jesus foretells his coming as that of "another Counselor" who, being the Spirit of truth, will lead the Apostles and the Church "into all the truth" (Jn 16, 13). This will be accomplished by reason of the particular communion between the Holy Spirit and Christ: "He will take what is mine and declare it to you" (Jn 16, 14). This communion has its original source in the Father: "All that the Father has is mine; therefore I said that he will take what is mine and declare it to you" (Jn 16, 15). Coming from the Father the Holy Spirit is sent by the Father (cf Jn 14, 26; 15, 26). The Holy Spirit is first sent as a gift for the Son who was made man, in order to fulfill the messianic prophecies. After the "departure" of Christ the Son, the Johannine text says that the Holy Spirit "will come" directly (it is his new mission), to complete the work of the Son. Thus it will be he who brings to fulfillment the new era of the history of salvation.

23. We find ourselves on the threshold of the Paschal events. The new, definitive revelation of the Holy Spirit as a Person who is the gift is accomplished at this precise moment. The Paschal events - the passion, death and resurrection of Christ - are also the time of the new coming of the Holy Spirit, as the Paraclete and the Spirit of truth. They are the time of the "new beginning" of the self-communication of the Triune God to humanity in the Holy Spirit through the work of Christ the Redeemer. This new beginning is the Redemption of the world: "God so loved the world that he gave his only Son" (Jn 3, 16). Already the "giving" of the Son, the gift of the Son, expresses the most profound essence of God who, as Love, is the inexhaustible source of the giving of gifts. The gift made by the Son completes the revelation and giving of the eternal love: the Holy Spirit, who in the inscrutable depths of the divinity is a Person-Gift, through the work of the Son, that is to say by means of the Paschal Mystery, is given to the Apostles and to the Church in a new way, and through them is given to humanity and the whole world.

24. The definitive expression of this mystery is had on the day of the Resurrection. On this day Jesus of Nazareth "descended from David according to the flesh," as the Apostle Paul writes, is "designated Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his Resurrection from the dead" (Rom 1, 3). It can be said therefore that the messianic "raising up" of Christ in the Holy Spirit reaches its zenith in the Resurrection, in which he reveals himself also as the Son of God, "full of power". And this power, the sources of which gush forth in the inscrutable Trinitarian communion, is manifested first of all in the fact that the Risen Christ does two things: on the one hand he fulfills God's promise already expressed through the Prophet's words: "A new heart I will give you, and a new spirit I will put within you,...my spirit" (Ez 36, 26; cf Jn 7, 37-39; 19, 34); and on the other hand he fulfills his own promise made to the Apostles with the words: "If I go, I will send him to you" (Jn 16, 7). It is he: the Spirit of truth, the Paraclete sent by the Risen Christ to transform us into his own risen image (St Cyril of Alexandria, In Ionnis Evangelium, V2).

"On the evening of that day, the first day of the week, the doors being shut where the disciples were, for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood among them and said to them, 'Peace be with you.' When he had said this, he showed them his hands and his side. Then the disciples were glad when they saw the Lord. Jesus said to them again, 'Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, even so I send you.' And when he had said this, he breathed on them, and said to them, 'Receive the Holy Spirit.'"86

All the details of this key-text of John's Gospel have their own eloquence, especially if we read them in reference to the words spoken in the same Upper Room at the beginning of the Paschal event. And now these events-the Triduum Sacrum of Jesus whom the Father consecrated with the anointing and sent into the world-reach their fulfillment. Christ, who "gave up his spirit" on the Cross87 as the Son of Man and the Lamb of God, once risen goes to the Apostles 'to breathe on them" with that power spoken of in the Letter to the Romans.88 The Lord's coming fills those present with joy: "Your sorrow will turn into joy,"89 as he had already promised them before his Passion. And above all there is fulfilled the principal prediction of the farewell discourse: the Risen Christ, as it were beginning a new creation, "brings" to the Apostles the Holy Spirit. He brings him at the price of his own "departure": he gives them this Spirit as it were through the wounds of his crucifixion: "He showed them his hands and his side." It is in the power of this crucifixion that he says to them: "Receive the Holy Spirit."

Thus there is established a close link between the sending of the Son and the sending of the Holy Spirit. There is no sending of the Holy Spirit (after original sin) without the Cross and the Resurrection: "If I do not go away, the Counselor will not come to you."90 There is also established a close link between the mission of the Holy Spirit and that of the Son in the Redemption. The mission of the Son, in a certain sense, finds its "fulfillment" in the Redemption. The mission of the Holy Spirit "draws from" the Redemption: "He will take what is mine and declare it to you."91 The Redemption is totally carried out by the Son as the Anointed One, who came and acted in the power of the Holy Spirit, offering himself finally in sacrifice on the wood of the Cross. And this Redemption is, at the same time, constantly carried out in human hearts and minds-in the history of the world-by the Holy Spirit, who is the "other Counselor. "

7. The Holy Spirit and the Era of the Church

25. "Having accomplished the work that the Father had entrusted to the Son on earth (cf. Jn 17:4), on the day of Pentecost the Holy Spirit was sent to sanctify the Church forever, so that believers might have access to the Father through Christ in one Spirit (cf. Eph 2:18). He is the Spirit of life, the fountain of water springing up to eternal life (cf. Jn 4:14; 7:38ff.), the One through whom the Father restores life to those who are dead through sin, until one day he will raise in Christ their mortal bodies" (cf. Rom 8:10f.).92

In this way the Second Vatican Council speaks of the Church's birth on the day of Pentecost. This event constitutes the definitive manifestation of what had already been accomplished in the same Upper Room on Easter Sunday. The Risen Christ came and "brought" to the Apostles the Holy Spirit. He gave him to them, saying "Receive the Holy Spirit." What had then taken place inside the Upper Room, "the doors being shut," later, on the day of Pentecost is manifested also outside, in public. The doors of the Upper Room are opened and the Apostles go to the inhabitants and the pilgrims who had gathered in Jerusalem on the occasion of the feast, in order to bear witness to Christ in the power of the Holy Spirit. In this way the prediction is fulfilled: "He will bear witness to me: and you also are witnesses, because you have been with me from the beginning."93

We read in another document of the Second Vatican Council: "Doubtless, the Holy Spirit was already at work in the world before Christ was glorified. Yet on the day of Pentecost, he came down upon the disciples to remain with them for ever. On that day the Church was publicly revealed to the multitude, and the Gospel began to spread among the nations by means of preaching."94

The era of the Church began with the "coming," that is to say with the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles gathered in the Upper Room in Jerusalem, together with Mary, the Lord's Mother.95 The time of the Church began at the moment when the promises and predictions that so explicitly referred to the Counselor, the Spirit of truth, began to be fulfilled in complete power and clarity upon the Apostles, thus determining the birth of the Church. The Acts of the Apostles speak of this at length and in many passages, which state that in the mind of the first community, whose convictions Luke expresses, the Holy Spirit assumed the invisible-but in a certain way "perceptible"-guidance of those who after the departure of the Lord Jesus felt profoundly that they had been left orphans. With the coming of the Spirit they felt capable of fulfilling the mission entrusted to them. They felt full of strength. It is precisely this that the Holy Spirit worked in them and this is continually at work in the Church, through their successors. For the grace of the Holy Spirit which the Apostles gave to their collaborators through the imposition of hands continues to be transmitted in Episcopal Ordination. The bishops in turn by the Sacrament of Orders render the sacred ministers sharers in this spiritual gift and, through the Sacrament of Confirmation, ensure that all who are reborn of water and the Holy Spirit are strengthened by this gift. And thus, in a certain way, the grace of Pentecost is perpetuated in the Church.

As the Council writes, "the Spirit dwells in the Church and in the hearts of the faithful as in a temple (cf. 1 Cor 3:16; 6:19). In them he prays and bears witness to the fact that they are adopted sons (cf. Gal 4:6; Rom 8:15-16:26). The Spirit guides the Church into the fullness of truth (cf. Jn 16:13) and gives her a unity of fellowship and service. He furnishes and directs her with various gifts, both hierarchical and charismatic, and adorns her with the fruits of his grace (cf Eph 4:11-12; 1 Cor 12:4; Gal 5:22). By the power of the Gospel he makes the Church grow, perpetually renews her and leads her to perfect union with her Spouse."96

26. These passages quoted from the Conciliar Constitution Lumen Gentium tell us that the era of the Church began with the coming of the Holy Spirit. They also tell us that this era, the era of the Church, continues. It continues down the centuries and generations. In our own century, when humanity is already close to the end of the second Millennium after Christ, this era of the Church expressed itself in a special way through the Second Vatican Council, as the Council of our century. For we know that it was in a special way an "ecclesiological" Council: a Council on the theme of the Church. At the same time, the teaching of this Council is essentially "pneumatological": it is permeated by the truth about the Holy Spirit, as the soul of the Church. We can say that in its rich variety of teaching the Second Vatican Council contains precisely all that "the Spirit says to the Churches"97 with regard to the present phase of the history of salvation.

Following the guidance of the Spirit of truth and bearing witness together with him, the Council has given a special confirmation of the presence of the Holy Spirit-the Counselor. In a certain sense, the Council has made the Spirit newly "present" in our difficult age. In the light of this conviction one grasps more clearly the great importance of all the initiatives aimed at implementing the Second Vatican Council, its teaching and its pastoral and ecumenical thrust. In this sense also the subsequent Assemblies of the Synod of Bishops are to be carefully studied and evaluated, aiming as they do to ensure that the fruits of truth and love-the authentic fruits of the Holy Spirit-become a lasting treasure for the People of God in its earthly pilgrimage down the centuries. This work being done by the Church for the testing and bringing together of the salvific fruits of the Spirit bestowed in the Council is something indispensable. For this purpose one must learn how to "discern" them carefully from everything that may instead come originally from the "prince of this world."98 This discernment in implementing the Council's work is especially necessary in view of the fact that the Council opened itself widely to the contemporary world, as is clearly seen from the important Conciliar Constitutions Gaudium et Spes and Lumen Gentium.

We read in the Pastoral Constitution: "For theirs (i.e., of the disciples of Christ) is a community composed of men. United in Christ, they are led by the Holy Spirit in their journey to the kingdom of their Father and they have welcomed the news of salvation which is meant for every man. That is why this community realizes that it is truly and intimately linked with mankind and its history."99 "The Church truly knows that only God, whom she serves, meets the deepest longings of the human heart, which is never fully satisfied by what the world has to offer."100 "God 's Spirit. . . with a marvelous providence directs the unfolding of time and renews the face of the earth."101

PART II - THE SPIRIT WHO CONVINCES THE WORLD CONCERNING SIN

1. Sin, Righteousness and Judgment

27. When Jesus during the discourse in the Upper Room foretells the coming of the Holy Spirit "at the price of" his own departure, and promises "I will send him to you," in the very same context he adds: "And when he comes, he will convince the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgment."102 The same Counselor and Spirit of truth who has been promised as the one who "will teach" and "bring to remembrance, " who "will bear witness," and "guide into all the truth," in the words just quoted is foretold as the one who "will convince the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgement."

The context too seems significant. Jesus links this foretelling of the Holy Spirit to the words indicating his "departure" through the Cross, and indeed emphasizes the need for this departure: "It is to your advantage that I go away, for if I do not go away, the Counselor will not come to you."103

But what counts more is the explanation that Jesus himself adds to these three words: sin, righteousness, judgment. For he says this: "He Will convince the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgment: concerning sin, because they do not believe in me; concerning righteousness, because I go to the Father, and you will see me no more; concerning judgment, because the ruler of the world is judged."104 In the mind of Jesus, sin, righteousness and judgment have a very precise meaning, different from the meaning that one might be inclined to attribute to these words independently of the speaker's explanation. This explanation also indicates how one is to understand the "convincing the world" which is proper to the action of the Holy Spirit. Both the meaning of the individual words and the fact that Jesus linked them together in the same phrase are important here.

"Sin," in this passage, means the incredulity that Jesus encountered among "his own," beginning with the people of his own town of Nazareth. Sin means the rejection of his mission, a rejection that will cause people to condemn him to death. When he speaks next of "righteousness," Jesus seems to have in mind that definitive justice, which the Father will restore to him when he grants him the glory of the Resurrection and Ascension into heaven: "I go to the Father." In its turn, and in the context of "sin" and "righteousness" thus understood, "judgment" means that the Spirit of truth will show the guilt cf the "world" in condemning Jesus to death on the Cross. Nevertheless, Christ did not come into the world only to judge it and condemn it: he came to save it.105 Convincing about sin and righteousness has as its purpose the salvation of the world, the salvation of men. Precisely this truth seems to be emphasized by the assertion that "judgment" concerns only the prince of this world," Satan, the one who from the beginning has been exploiting the work of creation against salvation, against the covenant and the union of man with God: he is "already judged" from the start. If the Spirit-Counselor is to convince the world precisely concerning judgment, it is in order to continue in the world the salvific work of Christ.

28. Here we wish to concentrate our attention principally on this mission of the Holy Spirit, which is "to convince the world concerning sin," but at the same time respecting the general context of Jesus' words in the Upper Room. The Holy Spirit, who takes from the Son the work of the Redemption of the world, by this very fact takes the task of the salvific "convincing of sin." This convincing is in permanent reference to "righteousness": that is to say to definitive salvation in God, to the fulfillment of the economy that has as its center the crucified and glorified Christ. And this salvific economy of God in a certain sense removes man from "judgment," that is from the damnation which has been inflicted on the Sill or Satan, "the prince of this world," the one who because of his sin has become "the ruler of this world of darkness."106 And here we see that, through this reference to "judgment," vast horizons open up for understanding "sin" and also "righteousness." The Holy Spirit, by showing sin against the background of Christ's Cross in the economy of salvation (one could say "sin saved"), enables us to understand how his mission is also "to convince" of the sin that has already been definitively judged ("sin condemned").

29. All the words uttered by the Redeemer in the Upper Room on the eve of his Passion become part of the era of the Church: first of all, the words about the Holy Spirit as the Paraclete and Spirit of truth. The words become part of it in an ever new way, in every generation, in every age. This is confirmed, as far as our own age is concerned, by the teaching of the Second Vatican Council as a whole, and especially in the Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et Spes. Many passages of this document indicate clearly that the Council, by opening itself to the light of the Spirit of truth, is seen to be the authentic depositary of the predictions and promises made by Christ to the Apostles and to the Church in the farewell discourse: in a particular way as the depositary of the predictions that the Holy Spirit would "convince the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgment."

This is already indicated by the text in which the Council explains how it understands the "world": "The Council focuses its attention on the world of men, the whole human family along with the sum of those realities in the midst of which that family lives. It gazes upon the world which is the theater of man's history, and carries the marks of his energies, his tragedies, and his triumphs; that world which the Christian sees as created and sustained by its Maker's love, fallen indeed into the bondage of sin, yet emancipated now by Christ. He was crucified and rose again to break the stranglehold of personified Evil, so that this world might be fashioned anew according to God's design and reach its fulfillment."107 This very rich text needs to be read in conjunction with the other passages in the Constitution that seek to show with all the realism of faith the situation of sin in the contemporary world and that also seek to explain its essence, beginning from different points of view.108

When on the eve of the Passover Jesus speaks of the Holy Spirit as the one who "will convince the world concerning sin," on the one hand this statement must be given the widest possible meaning, insofar as it includes all the sin in the history of humanity. But on the other hand, when Jesus explains that this sin consists in the fact that "they do not believe in him," this meaning seems to apply only to those who rejected the messianic mission of the Son of Man and condemned him to death on the Cross. But one can hardly fail to notice that this more "limited" and historically specified meaning of sin expands, until it assumes a universal dimension by reason of the universality of the Redemption, accomplished through the Cross. The revelation of the mystery of the Redemption opens the way to an understanding in which every sin wherever and whenever committed has a reference to the Cross of Christ-and therefore indirectly also to the sin of those who "have not believed in him," and who condemned Jesus Christ to death on the Cross.

From this point of view we must return to the event of Pentecost.

2. The Testimony of the Day of Pentecost

30. Christ's prophecies in the farewell discourse found their most exact and direct confirmation on the day of Pentecost, in particular the prediction which we are dealing with: "The Counselor...will convince the world concerning sin." On that day, the promised Holy Spirit came down upon the Apostles gathered in prayer together with Mary the Mother of Jesus, in the same Upper Room, as we read in the Acts of the Apostles: "And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance,"109 "thus bringing back to unity the scattered races and offering to the Father the first-fruits of all the nations."110

The connection between Christ's prediction and this event is clear. We perceive here the first and fundamental fulfillment of the promise of the Paraclete. He comes, sent by the Father, "after" the departure of Christ, "at the price of" that departure. This is first a departure through the Cross, and later, forty days after the Resurrection, through his Ascension into heaven. Once more, at the moment of the Ascension, Jesus orders the Apostles "not to depart from Jerusalem, but to wait for the promise of the Father"; "but before many days you shall be baptized with the Holy Spirit"; "but you shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the end of the earth."111

These last words contain an echo or reminder of the prediction made in the Upper Room. And on the day of Pentecost this prediction is fulfilled with total accuracy. Acting under the influence of the Holy Spirit, who had been received by the Apostles while they were praying in the Upper Room, Peter comes forward and speaks before a multitude of people of different languages, gathered for the feast. He proclaims what he certainly would not have had the courage to say before: Men of Israel,...Jesus of Nazareth, a man attested to you by God with mighty works and wonders and signs which God did through him in your midst...this Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men. But God raised him up, having loosed the pangs of death, because it was not possible for him to be held by it."112

Jesus had foretold and promised: "He will bear witness to me,...and you also are my witnesses." In the first discourse of Peter in Jerusalem this "witness" finds its clear beginning: it is the witness to Christ crucified and risen. The witness of the Spirit- Paraclete and of the Apostles. And in the very content of that first witness, the Spirit of truth, through the lips of Peter, "convinces the world concerning sin": first of all, concerning the sin which is the rejection of Christ even to his condemnation to death, to death on the Cross on Golgotha. Similar proclamations will be repeated, according to the text of the Acts of the Apostles, on other occasions and in various places.113

31. Beginning from this initial witness at Pentecost and for all future time the action of the Spirit of truth who "convinces the world concerning the sin" of the rejection of Christ is linked inseparably with the witness to be borne to the Paschal Mystery: the mystery of the Crucified and Risen One. And in this link the same "convincing concerning sin" reveals its own salvific dimension. For it is a "convincing" that has as its purpose not merely the accusation of the world and still less its condemnation. Jesus Christ did not come into the world to judge it and condemn it but to save it.114 This is emphasized in this first discourse, when Peter exclaims: "Let all the house of Israel therefore know assuredly that God has made him both Lord and Christ, this Jesus whom you crucified."115 And then, when those present ask Peter and the Apostles: "Brethren, what shall we do?" this is Peter's answer: "Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit."116

In this way "convincing concerning sin" becomes at the same time a convincing concerning the remission of sins, in the power of the Holy Spirit. Peter in his discourse in Jerusalem calls people to conversion, as Jesus called his listeners to conversion at the beginning of his messianic activity.117 Conversion requires convincing of sin; it includes the interior judgment of the conscience, and this, being a proof of the action of the Spirit of truth in man's inmost being, becomes at the same time a new beginning of the bestowal of grace and love: "Receive the Holy Spirit."118 Thus in this "convincing concerning sin" we discover a double gift: the gift of the truth of conscience and the gift of the certainty of redemption. The Spirit of truth is the Counselor.

The convincing concerning sin, through the ministry of the apostolic kerygma in the early Church, is referred-under the impulse of the Spirit poured out at Pentecost-to the redemptive power of Christ crucified and risen. Thus the promise concerning the Holy Spirit made before Easter is fulfilled: "He will take what is mine and declare it to you." When therefore, during the Pentecost event, Peter speaks of the sin of those who "have not believed"119 and have sent Jesus of Nazareth to an ignominious death, he bears witness to victory over sin: a victory achieved, in a certain sense, through the greatest sin that man could commit: the killing of Jesus, the Son of God, consubstantial with the Father! Similarly, the death of the Son of God conquers human death: "I will be your death, O death,"120 as the sin of having crucified the Son of God "conquers" human sin! That sin which was committed in Jerusalem on Good Friday-and also every human sin. For the greatest sin on man's part is matched, in the heart of the Redeemer, by the oblation of supreme love that conquers the evil of all the sins of man. On the basis of this certainty the Church in the Roman liturgy does not hesitate to repeat every year, at the Easter Vigil, "O happy fault!" in the deacon's proclamation of the Resurrection when he sings the "Exsultet. "

32. However, no one but he himself, the Spirit of truth, can "convince the world," man or the human conscience of this ineffable truth. He is the Spirit who "searches even the depths of God."121 Faced with the mystery of sin, we have to search "the depths of God" to their very depth. It is not enough to search the human conscience, the intimate mystery of man, but we have to penetrate the inner mystery of God, those "depths of God" that are summarized thus: to the Father-in the Son- through the Holy Spirit. It is precisely the Holy Spirit who "searches" the "depths of God," and from them draws God's response to man's sin. With this response there closes the process of "convincing concerning sin," as the event of Pentecost shows.

By convincing the "world" concerning the sin of Golgotha, concerning the death of the innocent Lamb, as happens on the day of Pentecost, the Holy Spirit also convinces of every sin, committed in any place and at any moment in human history: for he demonstrates its relationship with the Cross of Christ. The "convincing" is the demonstration of the evil of sin, of every sin, in relation to the Cross of Christ. Sin, shown in this relationship, is recognized in the entire dimension of evil proper to it, through the "mysterium iniquitatis"122 which is hidden within it. Man does not know this dimension-he is absolutely ignorant of it apart from the Cross of Christ. So he cannot be "convinced" of it except by the Holy Spirit: the Spirit of truth but who is also the Counselor.

For sin, shown in relation to the cross of Christ, is at the same time identified in the full dimension of the "mysterium pietatis,"123 as indicated by the Post- Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Reconciliatio et Paenitentia.124 Man is also absolutely ignorant of this dimension of sin apart from the Cross Christ. And he cannot be "convinced" of this dimension either, except by the Holy Spirit: the one who "searches the depths of God."

3. The Witness Concerning the Beginning: the Original Reality of Sin

33. This is the dimension of sin that we find in the witness concerning the beginning, commented on in the Book of Genesis.125 It is the sin that according to the revealed Word of God constitutes the principle and root of all the others. We find ourselves faced with the original reality of sin in human history and at the same time in the whole of the economy of salvation. It can be said that in this sin the "mysterium iniquitatis" has its beginning, but it can also be said that this is the sin concerning which the redemptive power of the "mysterium pietatis" becomes particularly clear and efficacious. This is expressed by St. Paul, when he contrasts the "disobedience" of the first Adam with the "obedience" of Christ, the second Adam: "Obedience unto death."126

According to the witness concerning the beginning, sin in its original reality takes place in man's will-and conscience-first of all as "disobedience," that is, as opposition of the will of man to the will of God. This original disobedience presupposes a rejection, or at least a turning away from the truth contained in the Word of God, who creates the world. This Word is the same Word who was "in the beginning with God," who "was God," and without whom "nothing has been made of all that is," since "the world was made through him."127 He is the Word who is also the eternal law, the source of every law which regulates the world and especially human acts. When therefore on the eve of his Passion Jesus Christ speaks of the sin of those who "do not believe in him," in these words of his, full of sorrow, there is as it were a distant echo of that sin which in its original form is obscurely inscribed in the mystery of creation. For the one who is speaking is not only the Son of Man but the one who is also "the first-born of all creation," "for in him all things were created ...through him and for him."128 In the light of this truth we can understand that the "disobedience" in the mystery of the beginning presupposes in a certain sense the same "non-faith," that same "they have not believed" which will be repeated in the Paschal Mystery. As we have said, it is a matter of a rejection or at least a turning away from the truth contained in the Word of the Father. The rejection expresses itself in practice as "disobedience," in an act committed as an effect of the temptation which comes from the "father of lies."129 Therefore, at the root of human sin is the lie which is a radical rejection of the truth contained in the Word of the Father, through whom is expressed the loving omnipotence of the Creator: the omnipotence and also the love "of God the Father, Creator of heaven and earth."

34. "The Spirit of God," who according to the biblical description of creation "was moving over the face of the water,"130 signifies the same "Spirit who searches the depths of God": "searches the depths of the Father and of the Word-Son in the mystery of creation. Not only is he the direct witness of their mutual love from which creation derives, but he himself is this love. He himself, as love, is the eternal uncreated gift. In him is the source and the beginning of every giving of gifts to creatures. The witness concerning the beginning, which we find in the whole of Revelation, beginning with the Book of Genesis, is unanimous on this point. To create means to call into existence from nothing: therefore, to create means to give existence. And if the visible world is created for man, therefore the world is given to man.131 And at the same time that same man in his own humanity receives as a gift a special "image and likeness" to God. This means not only rationality and freedom as constitutive properties of human nature, but also, from the very beginning, the capacity of having a personal relationship with God, as "I" and "you," and therefore the capacity of having a covenant, which will take place in God's salvific communication with man. Against the background of the "image and likeness" of God, "the gift of the Spirit" ultimately means a call to friendship, in which the transcendent "depths of God" become in some way opened to participation on the part of man. The Second Vatican Council teaches; "The invisible God out of the abundance of his love speaks to men as friends and lives among them, so that he may invite and take them into fellowship with himself."132

35. The Spirit, therefore, who "searches everything, even the depths of God," knows from the beginning "the secrets of man."133 For this reason he alone can fully "convince concerning the sin" that happened at the beginning, that sin which is the root of all other sins and the source of man's sinfulness on earth, a source which never ceases to be active. The Spirit of truth knows the original reality of the sin caused in the will of man by the "father of lies," he who already "has been judged."134 The Holy Spirit therefore convinces the world of sin in connection with this "judgment," but by constantly guiding toward the "righteousness" that has been revealed to man together with the Cross of Christ: through "obedience unto death."135

Only the Holy Spirit can convince concerning the sin of the human beginning, precisely he who is the love of the Father and of the Son, he who is gift, whereas the sin of the human beginning consists in untruthfulness and in the rejection of the gift and the love which determine the beginning of the world and of man.

36. According to the witness concerning the beginning which we find in the Scriptures and in Tradition, after the first (and also more complete) description in the Book of Genesis, sin in its original form is understood as "disobedience," and this means simply and directly transgression of a prohibition laid down by God.136 But in the light of the whole context it is also obvious that the ultimate roots of this disobedience are to be sought in the whole real situation of man. Having been called into existence, the human being-man and woman-is a creature. The "image of God," consisting in rationality and freedom, expresses the greatness and dignity of the human subject, who is a person. But this personal subject is also always a creature: in his existence and essence he depends on the Creator. According to the Book of Genesis, "the tree of the knowledge of good and evil" was to express and constantly remind man of the "limit" impassable for a created being. God's prohibition is to be understood in this sense: the Creator forbids man and woman to eat of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. The words of the enticement, that is to say the temptation, as formulated in the sacred text, are an inducement to transgress this prohibition-that is to say, to go beyond that "limit": "When you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God ["like gods"], knowing good and evil."137

"Disobedience" means precisely going beyond that limit, which remains impassable to the will and the freedom of man as a created being. For God the Creator is the one definitive source of the moral order in the world created by him. Man cannot decide by himself what is good and what is evil-cannot "know good and evil, like God." In the created world God indeed remains the first and sovereign source for deciding about good and evil, through the intimate truth of being, which is the reflection of the Word, the eternal Son, consubstantial with the Father. To man, created to the image of God, the Holy Spirit gives the gift of conscience, so that in this conscience the image may faithfully reflect its model, which is both Wisdom and eternal Law, the source of the moral order in man and in the world. "Disobedience," as the original dimension of sin, means the rejection of this source, through man's claim to become an independent and exclusive source for deciding about good and evil The Spirit who "searches the depths of God," and who at the same time is for man the light of conscience and the source of the moral order, knows in all its fullness this dimension of the sin inscribed in the mystery of man's beginning. And the Spirit does not cease "convincing the world of it" in connection with the Cross of Christ on Golgotha.

37. According to the witness of the beginning, God in creation has revealed himself as omnipotence, which is love. At the same time he has revealed to man that, as the "image and likeness" of his Creator, he is called to participate in truth and love. This participation means a life in union with God, who is "eternal life."138 But man, under the influence of the "father of lies," has separated himself from this participation. To what degree? Certainly not to the degree of the sin of a pure spirit, to the degree of the sin of Satan. The human spirit is incapable of reaching such a degree.139 In the very description given in Genesis it is easy to see the difference of degree between the "breath of evil" on the part of the one who "has sinned (or remains in sin) from the beginning"140 and already "has been judged,"141 and the evil of disobedience on the part of man.

Man's disobedience, nevertheless, always means a turning away from God, and in a certain sense the closing up of human freedom in his regard. It also means a certain opening of this freedom-of the human mind and will-to the one who is the "father of lies." This act of conscious choice is not only "disobedience" but also involves a certain consent to the motivation which was contained in the first temptation to sin and which is unceasingly renewed during the whole history of man on earth: "For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil."